Sometimes our work takes on a life of its own, and we can do nothing but wonder at how others might interpret it.

Read moreStudying Philosophy and Religion...all that different?

After completing three degrees in religious studies (BA, MTS, PHD), this year I find myself teaching in a philosophy department. In the particular case of UC Colorado Springs (UCCS), there is no formal religious studies program on campus, and the philosophy department is the place where the study of religion has found a proverbial home. After visiting campus for the first time a few weeks ago (see my earlier blog post) and meeting some of the philosophy faculty, I have to say I didn’t feel out of place at all. After all, the dividing line between these two disciplines is largely arbitrary, and can be traced to particular social and cultural histories in European and North American academies. Especially after attending Harvard Divinity School, which some forget is technically a seminary, I came to appreciate how many subjects philosophers and theologians have in common, and how religious studies as an academic discipline overlaps with both while also retaining some space of its own. At dinner with my colleagues, I was amazed at how many people told me about their love for teaching al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Ibn Sina (the name I prefer to the Latin transliteration, Avicenna, but that’s a different blog post).

I developed a course called Islamic Philosophy for UCCS this semester, and will be teaching another course called Modern Islamic Philosophy in the fall. So far, the syllabus each course (one in progress and one under development) is not that different from a course I took at Harvard called…wait for it…”Islamic Philosophy and Theology.” Reading al-Kindi, al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, al-Ghazali, Ibn Rushd, Mulla Sadra, Sayyid Ahmed Khan, Muhammad `Abdu, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Said Qutb, and so forth in one department vs. another is not that different, especially at the undergraduate level. True, most of my students at UCCS have taken philosophy courses before, and have more familiarity with Aristotle than you would expect from the typical 21 year old in the United States, but almost none of them have read anything from Islamic intellectual history before, so that previous knowledge only serves them when the authors we cover in class address the Greek “classical” writers. The rest of the time, I have to explain everything else the same way I would when teaching this material in a religious studies department.

In terms of scholarship, my training and specialization is in studying texts, analyzing them in order to produce new insights — either because no one else has looked at the texts in question for a very long time, or because I seek to make an intervention in the current scholarly discourse surrounding the subjects that these texts address. So, studying Indian divination techniques known as “the science of the breath” (Persian: `ilm-i dam), brings up these challenging questions - how do we draw the boundaries between science, religion, and magic? How do those boundaries shift from one historical or cultural context to another? What happens when we take boundaries generated in a particular context and apply them to another without adjusting for different political and religious sensibilities? What role does colonization and Orientalism play in the way that knowledge from non-European cultures has been received, interpreted, and marginalized - especially over the past 300 years? These are all questions that I know I can pursue in cooperation with this band of philosophers with whom I now find myself joined.

In truth, after spending five years immersed in a religious studies program, it has been a breath (ha!) of fresh air to change gears. I’m reminded of my undergraduate institution, Macalester College (Go Scots!), where the Departments of Religious Studies and Philosophy shared the same floor in Old Main, and I was known to bother professors from either department if they left the door open…inviting me to stop by and ask questions. In addition to religious studies, I also majored in classics, and read some of these ancient philosophers in the original Greek.

This is all to say that in my experience, a scholar of religion teaching in a philosophy department is no “stranger in a strange land” situation. Instead, I think it is a real opportunity for growth. I get to talk to people who have spent a lot of time analyzing texts, but also considering other approaches to knowledge (embodiment and visual/material culture especially). We sit, we think, we ask questions. We want to know more, understand more, question more. Sounds like “love of wisdom” (philo-sophia) to me.

AAR 2018!

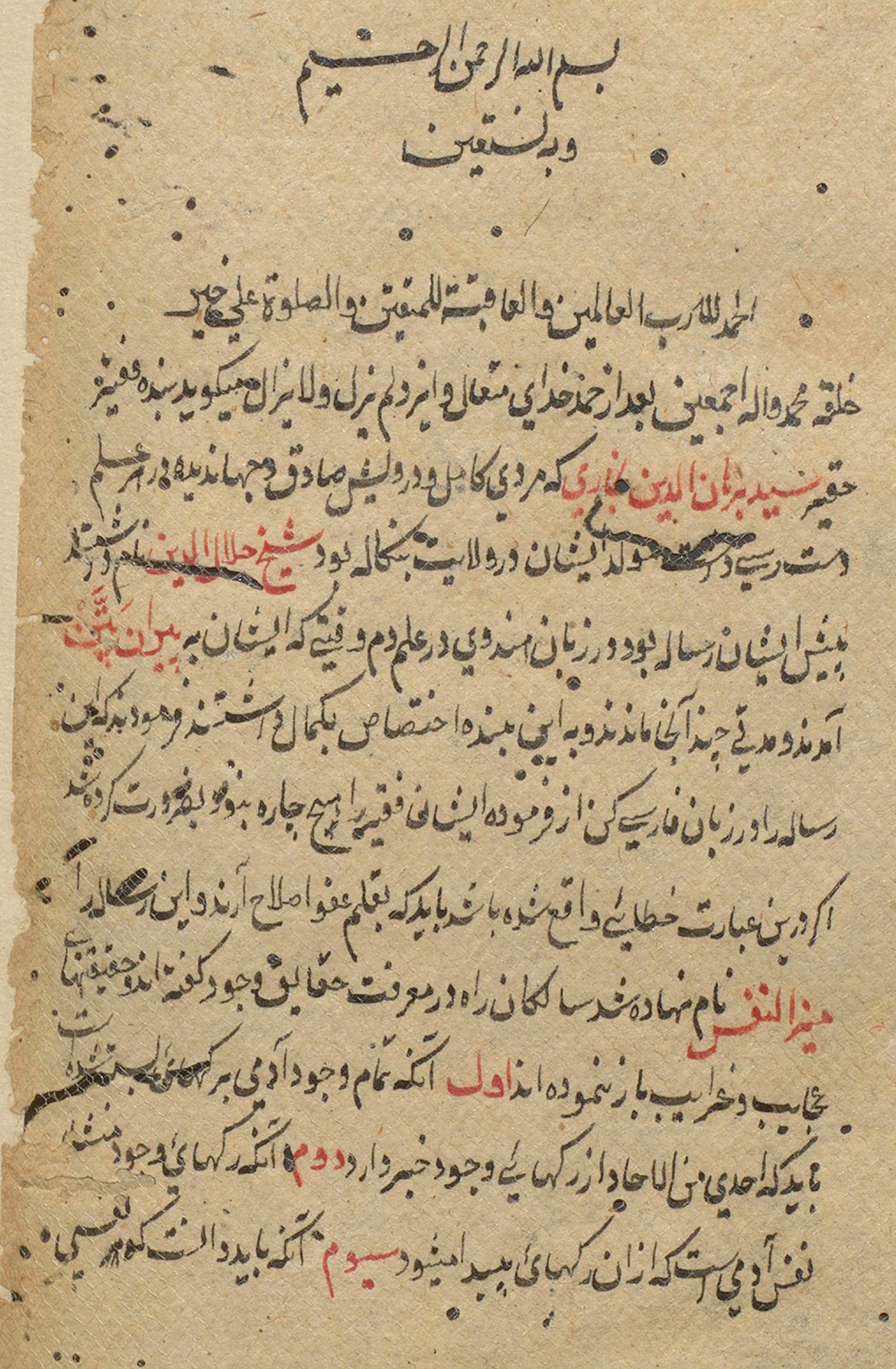

As always, I am excited to attend the annual American Academy of Religion (AAR - https://www.aarweb.org/annual-meeting) conference. This year it is in Denver, Colorado (so close to home!), running from November 17-20, 2018. I will be presenting a paper entitled “Bodies in Translation: Esoteric Conceptions of the Muslim Body in Early-modern South Asia” as part of the Material Islam seminar. The theme for this year’s session was the body, and I was thrilled that the organizers accepted my proposal. My paper draws on one of my dissertation chapters, in which I analyze how the esoteric breathing practices known in Persian as `ilm-i dam (“the science of the breath”) complicate our understanding of religious boundaries in South Asia. I am looking forward to reconnecting with friends and colleagues during the conference. If you’re interested in hearing more, come sit in on the panel! We meet on Monday, November 19th, 9:00-11:30 a.m., Denver Convention Center-707 (street level). As a teaser, here is a key quote from one of the manuscripts I discuss in the paper, along with a photo of the folio from which this quote is taken:

“First, that the entire human body is held together with veins (rig-ha).

It is necessary that one of these veins has information (khabar).

Second, namely that the veins of the body are the source of the human breath, which appears from those veins.

Third, one should know that each breath (nafas) individually goes by three paths.

The first is from the right side, they say it is of the sun.

The second is from the left side, they say it is of the moon.

The third is in the middle of two nostrils, they say it is heavenly (asmani).

Every breath (dam) has a special quality.”

Miz al-Nafas, British Library Delhi Persian 796d (London), folio 57b-58a.

Reflections on the 5th Perso-Indica conference

I recently had the opportunity to participate in the 5th Perso-Indica conference, hosted by Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Bonn, Germany. The Perso-Indica project (http://perso-indica.net/) is a long term undertaking aimed at improving our understanding of knowledge production and circulation within the Persianate cosmopolis during the pre- and early-modern era. The project will result in a massive online database, as well as a series of published volumes. This particular conference focused on the translation of scientific texts.

I presented a paper entitled "The Philosophical Implications of Classifying `ilm-i dam as 'Science'." The paper examined three different texts on "the science of the breath" (Persian: `ilm-i dam) from the 14th-17th CE. If you are interested in more information, the full program and paper abstracts are available on the Perso-Indica website (http://perso-indica.net/events-news/31).

This was my first time attending such a highly specialized academic conference. In the past I have attended large conferences organized by the American Academy of Religion (AAR) and the Middle Eastern Studies Association (MESA), as well as smaller regional conferences sponsored by AAR. The contrast between those experiences and attending the Perso-Indica conference were quite striking. At AAR, I find myself constantly having to explain not only what I work on, but also having to justify why it is a meaningful scholarly pursuit. At the larger conferences, there is a great deal of networking and the opportunity to learn from people working outside of one's own niche field, and of course, who doesn't want to spend a few days with 10,000 people who also love to talk about the study of religion?

In Bonn, I spent two days talking to a small group of people who (1) understood and appreciated the importance of my work, and (2) were in a position to give me incredibly helpful feedback as well as offer detailed suggestions for my research. By detailed suggestions, I mean that during coffee breaks, scholars would pass me notes with manuscript references taken from their own archival work, as well as the now ubiquitous passing around of USB drives so that we could exchange scanned images of manuscripts. When many of the texts in question have never been published (and thus exist only in physical form), and traveling in person to research institutes across the world is a bit of a stretch on a graduate student budget, then these exchanges are a wonderful way to be able to advance one's research. Also, whereas at AAR and MESA, there is a constant shuffle as people come in and out of the conference rooms, during the sessions in Bonn, no one ever left the room. Everyone attending was focused on listening to the paper being presented, and as a result there was extremely fruitful discussion.

There are benefits to all types of scholarly gatherings, but I have to admit that I found the Perso-Indica conference to be the most satisfying of such experiences to date. I look forward to staying in touch with a whole group of colleagues, and to the future projects that will doubtlessly result from productive exchange.